The onset of Covid-19 marked an exceptional time in history. While economic activity slumped, fiscal and monetary policy across the globe stepped up to save growth/livelihoods and minimise the impact of what could have been an economic catastrophe.

Unlike the many developed markets where the support lines were opened fairly quickly, India had to wait a few months for the relief packages to come in.

Economists pointed out that, while India announced many packages, the net fiscal impact has been small. So when the world starts rolling back its fiscal support, India has a little less to worry on the fiscal front since there isn’t much to roll back. India, instead, used the opportunity well to do structural reforms, which are likely to benefit the country in coming years of growth.

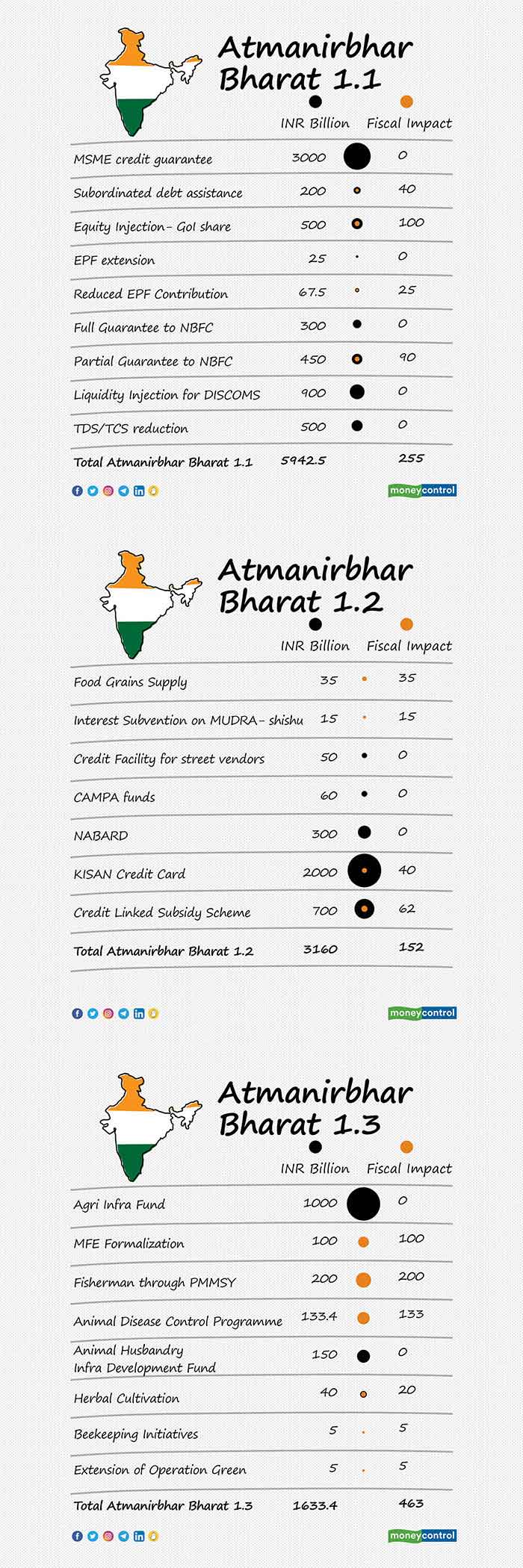

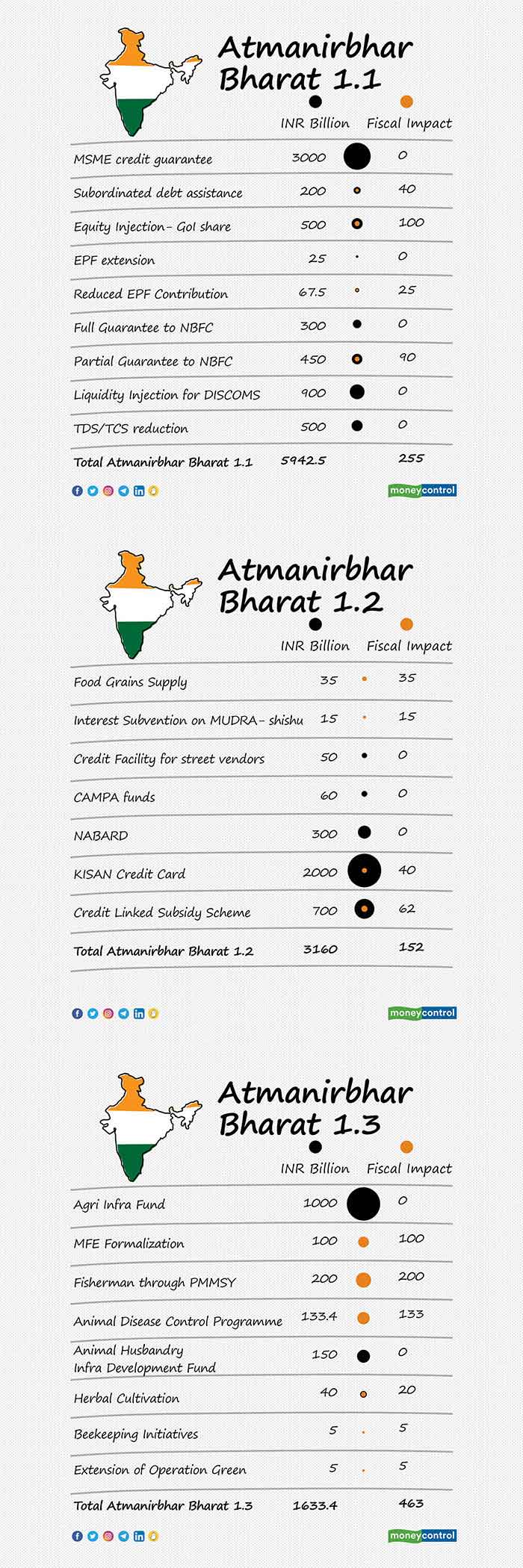

Major relief packages were announced under the Atmanirbhar umbrella, the breakup of which is as follows:

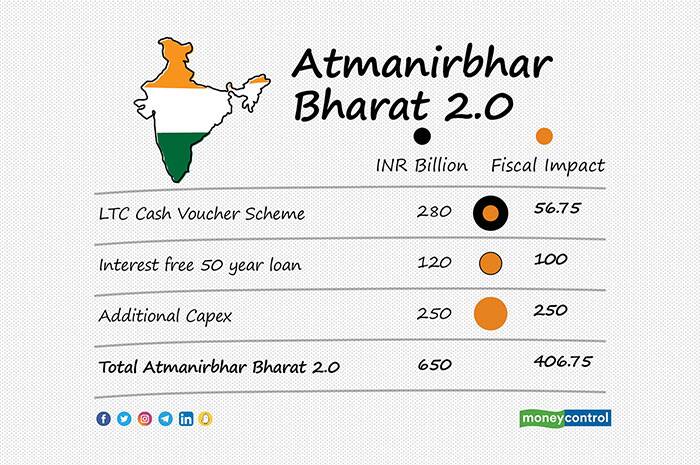

After the first package in May 2020, the second or Atmanirbhar Bharat 2.0 was announced in October 2020…

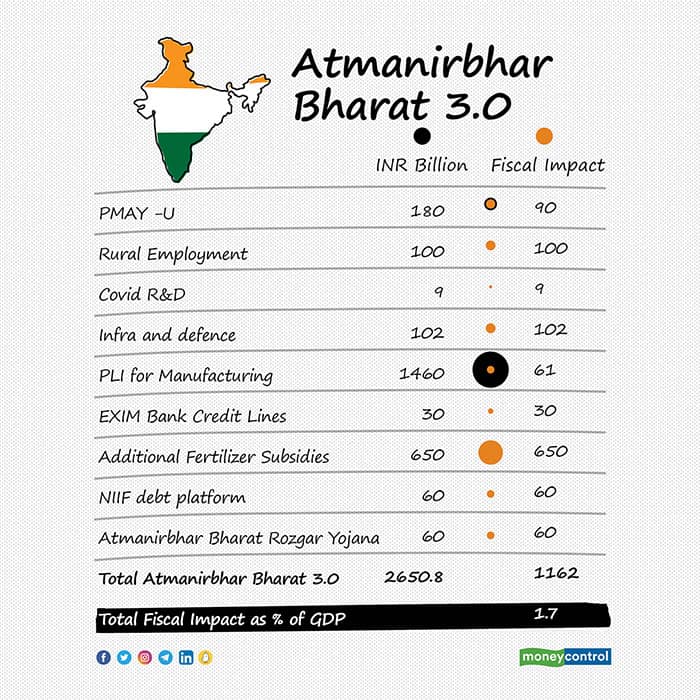

…and the third or Atmanirbhar Bharat 3.0 was announced in November 2020.

To explain this a bit further, let’s look at a few of the interventions and see why they didn’t cost the government too heavily.

One, the Emergency Credit Guarantee Scheme had an outlay of Rs 3 trillion, but it did not really involve fiscal expenditure from government’s coffers. Its fiscal liability would only arise if the beneficiaries or MSMEs were unable to pay the money back. Two, the Agriculture Infra Fund, where the beneficiaries could avail mid-to-long term loans at lower costs, had an outlay of Rs 1 trillion. Again, these are loans, so no fiscal expenditure is involved. Three, the Rs 900 billion liquidity injection into DISCOMS. It was to be raised from the markets against DISCOMS’ receivables and they were guaranteed by the state.

Clearly, all the announcements led to a relatively small fiscal burden–of 1.7% of GDP or roughly Rs 3.4 trillion.

Did all of it reflect in government expenditure?

When the GoI made the Budget for FY21 pre-Covid, total budgeted expenditure was Rs 30.4 trillion. But, the actual FY21 expenditure came in at Rs 34.5 trillion. For FY22, the Budget figure stood at Rs 34.8 trillion. This year Covid sops stand close to Rs 2 trillion, but GoI has been relatively sparing with other expenditures so the overall numbers are likely to remain within ‘bounds’. Therefore, the chance of the government meeting its expenditure estimates looks bright. In Apr-Oct FY22, GoI used 46% of its budgeted capital expenditure and 54% of its budgeted revenue expenditure.

On the expenditure side, vaccine coverage was being keenly watched. For FY22, Rs 350 billion was set aside in the government budget. Then, with the announcement of free vaccination for those above 18 years, the outlay was revised to Rs 500 billion. However, the government seems to have spent much lesser than these estimates.

In a response to a RTI, the government has said Rs 197 billion has been spent thus far for the 117.56 crore doses, for 96.5% of the population, administered at government Covid Vaccination Centres (CVCs) from May 1 to December 20.

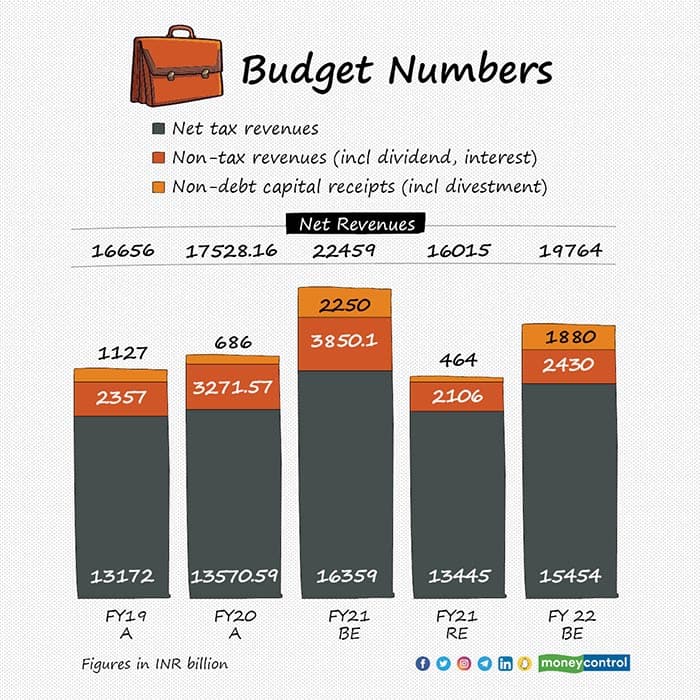

Breakdown of revenues

With economic activity limited to essential sectors, the impact of the pandemic on revenue (especially taxes) for FY21 was significant.

In FY21, net revenues were down by Rs 6.4 trillion or 30% lower than budgeted. The big culprit was of course the tax revenue which was lower by Rs 5 trillion. The reasons were pretty obvious–with limited economic activity, reduced profits and reduced income, the tax liability of the economy slumped.

However, FY22 started on an optimistic note, as far as government revenue was considered. The April-October tax collections stand at Rs 13.6 trillion, obviously higher than the collections for the same period in FY21 at Rs 8.8 trillion but also higher than pre-Covid averages of Rs 10 trillion.

At this run rate, the government is set to meet and in fact exceed its budgeted tax collections of Rs 22.1 trillion in FY22.

Higher corporate earnings and increased tax collections in excise duties as the oil prices remained low helped the government in bulking up the tax collections. On the other hand, even non-tax revenue is painting a sunny picture, with talks of disinvestment picking pace. If even one of the big deals such as Air India comes through, revenue projections of the year will be met. Overall, chances are bright that the fiscal deficit for the year could settle lower at 6.5% versus the 6.8% that was budgeted.

India versus world

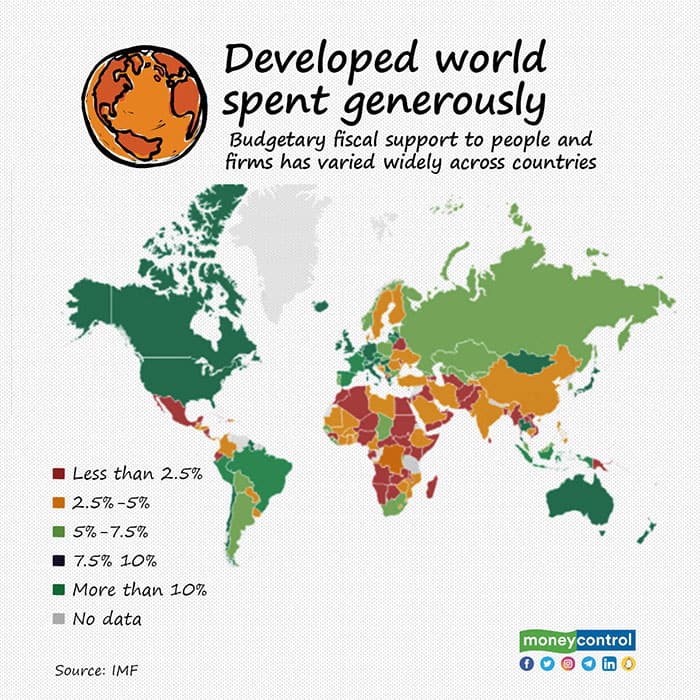

There was a vast dichotomy between the way the developed world responded–by spending its way out of the pandemic–and the emerging economies acted, which remained relatively cautious.

Most emerging economies extended little help by way of direct fiscal allocation. They chose instead to tread the path of equity, loans and guarantees, such as the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS) we saw in India.

On an average, advanced economies gave direct support worth 12% of GDP, and equity, loans and guarantee worth another 11% of GDP. Averages of emerging economies–at 6% of GDP in direct fiscal support and 4% in equity, loans and guarantees–don’t reflect the general trend, since they were skewed by higher spending by a few countries on direct support. That said, India spent an additional 4% of GDP (over the average) in fiscal support and there will be an additional 6.2% infused through equity, loans and guarantees.

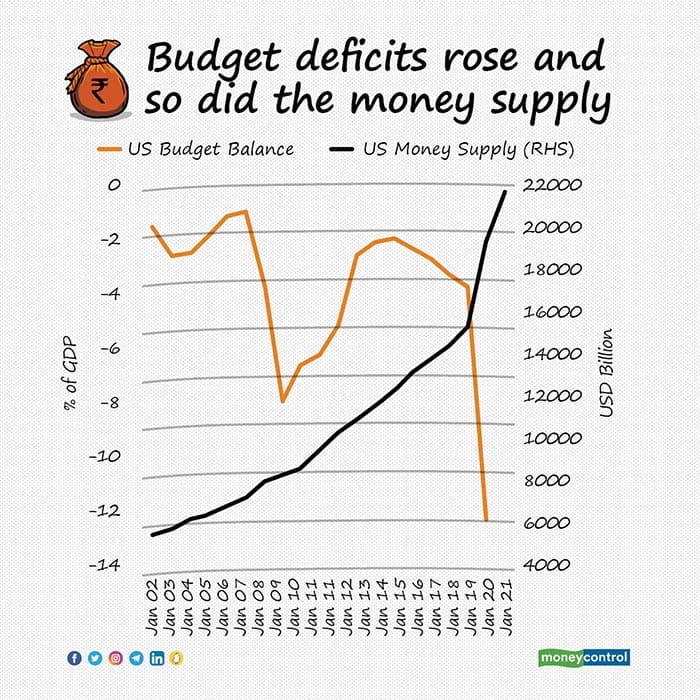

The key question then remains–who funded these huge deficits? Traditionally, there are tax-based, expenditure-based and debt-based approaches to deficit financing. This year, given the pandemic, all the traditional approaches had a limited and difficult application.

Neither the tax could be raised nor expenditure be curtailed and, if debt was increased, who would absorb the supply anyway? This was the year when MMT (modern monetary theory) dominated the economic landscape. Modern monetary theory says that the government can simply print the money it needs to borrow, and need not issue bonds at all.

For most of the developed worlds, it was the central banks who financed the deficit by printing more money via the Quantitative Easing route. For example, for the United States, not only did the fiscal balance turn deep negative, the printing even kept the money supply soaring.

As the pandemic recedes, this approach is likely to change. There is a likely chance of higher taxes for the rich to absorb the higher debt faster.

Developing world was more constrained in its options, not wanting to raise its fiscal deficit astronomically. They had to fund it through domestic supply. Going forward, we could have higher taxes for the rich, issuing bonds, attracting foreign capital and ensuring better tax administration, among other things. Most importantly, it should not abruptly withdraw fiscal support and should work in the direction of creating resources for long-term, sustainable debt management.

Covid inequalities

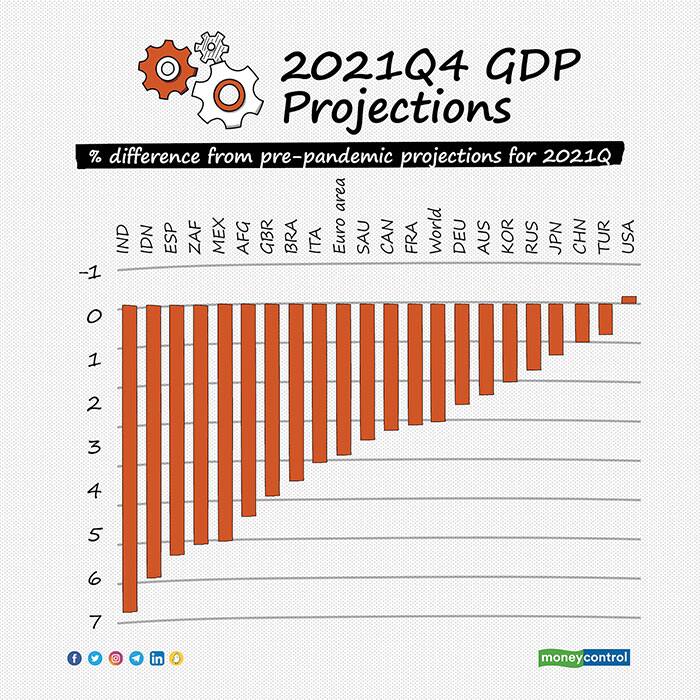

The pandemic forced nations and their central banks to think out of the box, but among its many flipsides was the deepening of economic disparities.

Simply put, it made the weak weaker. A look at the global output losses demonstrate that it is the developing world where the pain has been most intense, even in the most recent time (Q4 CY21)

Meanwhile, billionaires gained more wealth.

Forbes 2021 listed 2,755 billionaires with a total net wealth of $13.1 trillion, which is a jump up from 660 billionaires from 2020; 86% of these billionaires had more wealth than they possessed last year. Clearly, the richest were saved from the many woes of the pandemic, amidst wealth multiplication and asset-price inflation.

Wealth multiplier effect is when the returns earned by personal wealth is greater than the national growth rate. Asset-price inflation can happen when interest rates fall– then investors move away from interest-earning assets and flock to other financial assets such as equity and real estate, driving up their prices.

In India, the widening inequality was stark. As per a study by IdeasforIndia, percentage of households that have an average monthly income below Rs. 4,000 per capita (for a typical family of four this is equivalent to Rs. 16,000) increased in the Covid-19 months – from roughly 50% in pre-Covid-19 period to close to 65% during the Covid-19 period in rural India.

Additionally, the difference between the top 10% and bottom 50% in income share widened to levels last seen in the colonial period. The K-shaped recovery India witnessed undid the years of work on reducing inequality and deepened the existing scars.

There’s also a vast inequality that prevailed among the genders, with unemployment being much higher than male employment.

What next?

It is an interesting question to ponder over. Covid-19 has put us on a two-track recovery.

While the next five years or so will flourish to undo the damage caused by Covid-19, both on income inequalities and on economies as a whole, the road to it will be an interesting one.

Sustainable debt management will take centrestage. While fiscal push will slowly wane, monetary policy across the globe could diverge. India, for instance, can choose to be accommodative for longer and could keep the liquidity in surplus.

Fiscal policy will be laid down in February, 2022, and chances are high for the policy to support the poor. Vast output gaps–the difference between an economy’s potential output and its actual output–will start to shrink and hopefully part of the output recovery will translate into better jobs prospects. India has done many structural reforms such as production-linked incentive scheme (PLIS), exports promotion, Make in India initiative and manufacturing tax holidays.

A rickety recovery road lies ahead of us!

This article was originally published on Moneycontrol. See original >