Every year, the union budget invites a significant amount of noise, right from the speculations to very specific sectoral asks. Every year, it is a tightrope walk between limited resources and the ever increasing need for expenditure.

The ground reality is that the Budget isn’t a festival of bumper-dhamaka offers. It is more like an annual conference, where the CFO gives an account of the finances. Transparency and credibility are key.

Therefore, even a non-event budget is a good budget.

For those of us who find the budget clamour too disorienting, here are the four simple things to look out for.

Are the revenue sources credible?

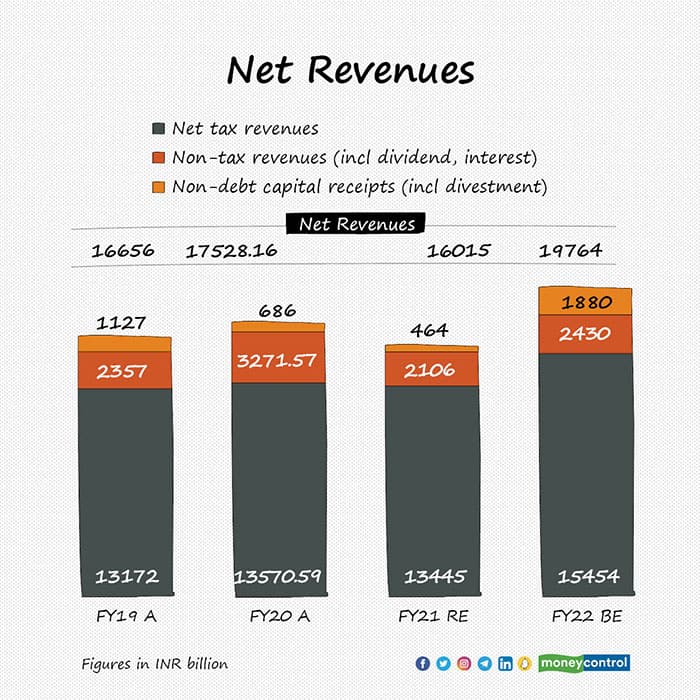

Government’s budget has three parts on the revenue side–a) tax revenue b) non-tax revenue such as dividends and interests and c) disinvestments.

To understand if the tax-revenue estimates are plausible, you need to read it against the nominal GDP numbers.

Nominal GDP growth could be around 14% in FY23. From this you approximate the nominal GDP for the fiscal and from that you can calculate what would be the tax revenue–usually around 10-11% of the nominal GDP, since India’s tax-to-GDP ratio roughly is in that range. Mostly income taxes, corporate taxes and GST grow at similar rates, unless the government expects GST to be much higher. It could expect higher GST collections, if it is considering raising tax rates or expects a significant jump in compliance. It could also expect lower GST collections, if it is exempting certain categories from this tax.

Similarly, the government’s projections of the excise-duty collections can tell you about its expectations about global oil prices and the taxes it wishes to charge. For example, projections could be higher if it is expecting the global oil prices to go up or if it means to raise taxes. Technically, its projections of excise-duty collections could also be higher if it is expecting a higher oil demand, but this is unlikely given oil demand is inelastic.

Then, there are transfers made to the states to be considered, to arrive at the centre’s net tax revenue. Ideally, the centre should stick to its commitments on revenue sharing. Gross tax revenue for FY22 is budgeted at Rs 22.2 tn. In this, budgeted state transfers were Rs 6.7 tn, which leaves centre’s net tax revenue at Rs 15.5 tn.

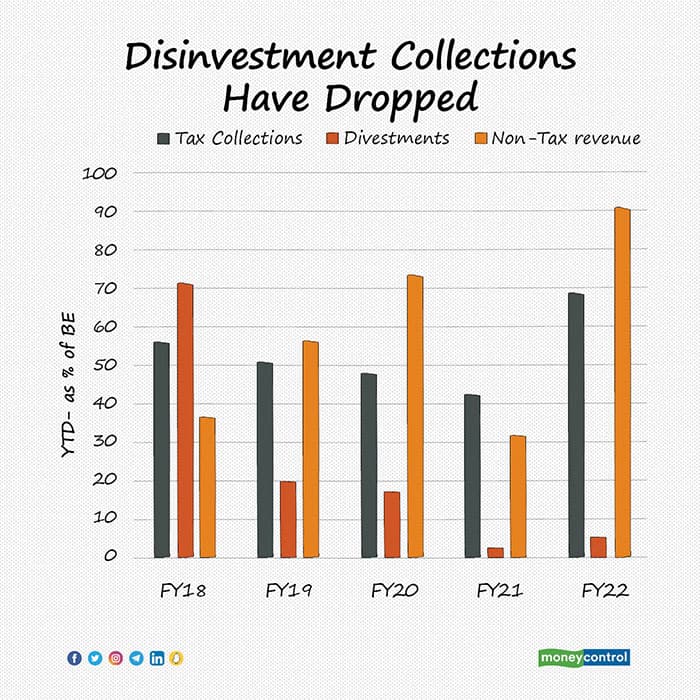

Additionally, non-tax revenue–which includes dividends from RBI and public sector institutions–should be read against the government’s historical track record. For FY22, this number stood at Rs 2.4 trillion. Divestments were budgeted at Rs 1.8 trillion for FY22 but only about 5% of the target was met. Therefore, divestments number could be high because some of FY22 pending deals could now roll into FY23.

Overall, when revenue sources appear credible, it will instil trust in the economy and drive investments.

Where is the money going?

These are the numbers that usually make the headlines. This is because overall expenditure numbers are seen as an impetus given to the economy.

FY22 expenditure was budgeted at Rs 34.7 trillion, so we can reasonably expect around 12% increase on that. Anything more would be difficult because resources are limited and fiscal deficit is a key constraint.

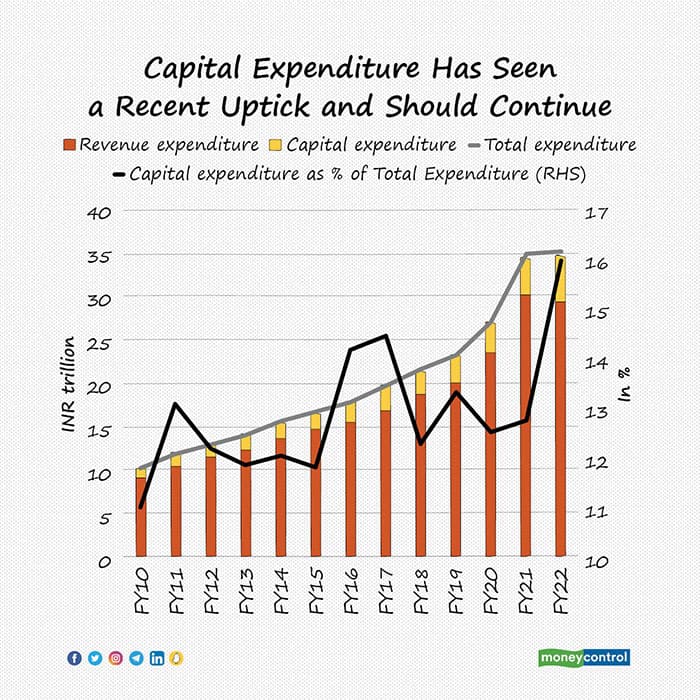

But, more than this headline, you need to pay closer attention to how it will be split. That is, how much would be revenue expenditure and how much would be capital expenditure?

Revenue expenditure is what groceries and utilities are to the households. They are a must–like how you cannot do without rice/wheat and electricity. In FY22, revenue expenditure stood at Rs 29.2 tn of which Rs 8 tn was interest payments and some Rs 3 tn was spent on subsidies. The remaining is mostly to meet the expenditure of the government and for allocation to schemes such as MGNREGA and PM KISAN.

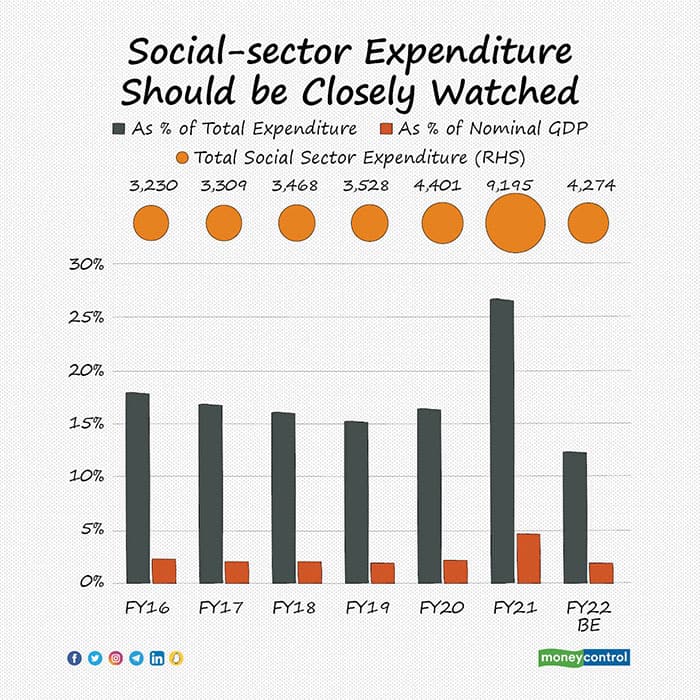

Given that this is the election year of seven key states, keep an eye out for extravagant, populist schemes. Social-sector expenditure of the government went up to 4% of GDP in FY21 but this should be brought down to 2-2.5% of GDP hereon. Any significant changes in this percentage should be thoroughly analysed.

Now comes the capital expenditure.

It is what is spent on buying longer-term, value-generating assets–like a person would buy a washing machine or a vacuum cleaner. The government’s capex would be building roads, railways, ports and so on. It has a higher growth multiplier because it helps to build durable assets and create jobs in the economy.

Government’s capex is what has kept the economy going in the past decade because private investments have been subdued. Recently, the capex push and allocation from the centre has gone up and now stands at Rs 5.5 trillion. This number should rise significantly this year.

These are capital expenditures that are easily visible. What is interesting is the capex that is hidden.

For example, instead of GOI allocating a budget for Rail Corporation, Rail Corporation could raise money on its own balance sheet. Such an entry is called Internal and Extra Budgetary Resources (IEBR) and should be noted to understand the total capex allocation.

The flipside of IEBR is that it balloons borrowing, causes crowding out of private-sector borrowings, increases interest burden on all players and makes these PSUs vulnerable. Therefore, IEBR should be limited but should be fully taken into account to understand the overall complexion of the budget. In FY22, IEBR in capex stood close to Rs 5.1 trillion, which is a massive increase from Rs 3.4 trillion in FY17.

What is the fiscal deficit?

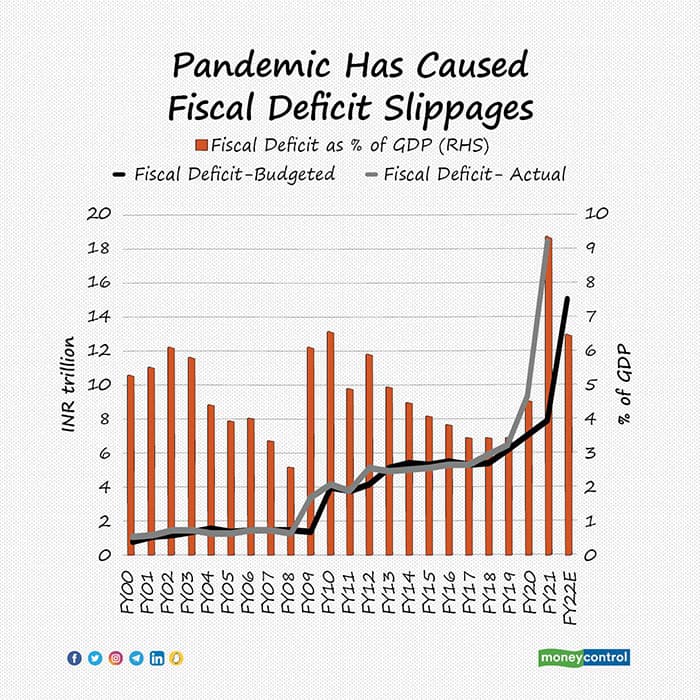

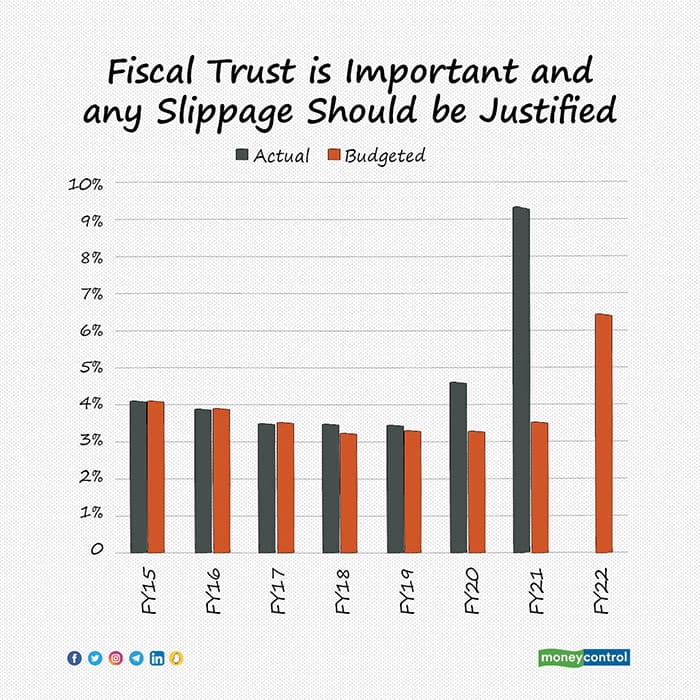

Literally, every Union Budget is a fine balancing-act and the magic of it is revealed in the fiscal-deficit number.

There’s no right or wrong fiscal-deficit figure. Its rightness depends on the domestic need and global scenario.

To interpret the fiscal deficit number, keep an eye on the credit ratings of the country. If the rating is high, borrowing costs go down and debt-servicing burden goes down with it.

Of course, we are passing through an unprecedented crisis. So, credit ratings are being more accomodating of high fiscal deficits and countries’ ballooning balance sheets.

In fact, fiscal deficit becomes a must to fuel the domestic economy. That said, a country can’t miss its fiscal deficit target willy nilly. These misses have to be adequately justified.

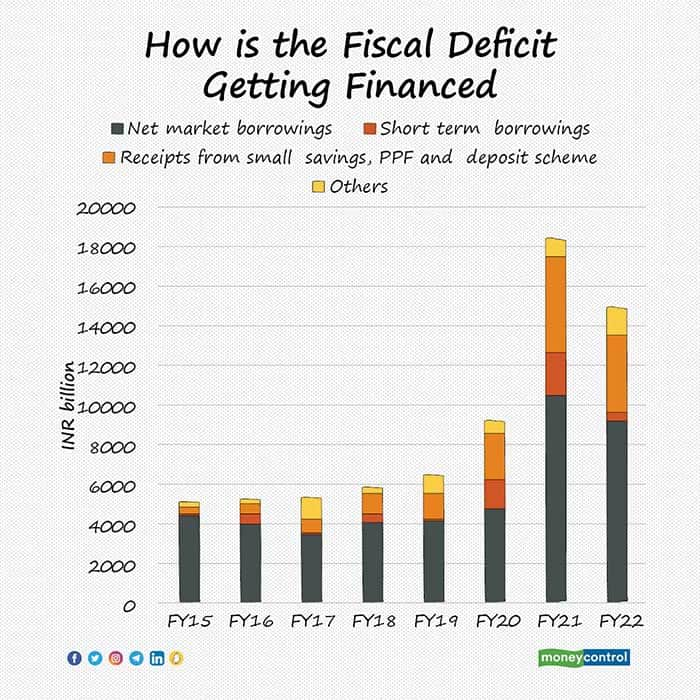

4. How is the fiscal deficit being financed?

While the headline number is important, what is more important to know is if the economy can afford it.

Borrowing is fine as long as it can be credibly financed.

India has been financing a chunk of its deficit through domestic market borrowings and small savings funds. It could also raise money internationally through specific bonds, though India hasn’t ventured in that direction yet. This is because, while international borrowing could be cheap, increasing foreign currency debt creates exchange rate risk. After the Balance of Payments crises of FY91, India has adopted a rather conservative stance on foreign borrowing.

The key questions will then be if there will be enough demand for government borrowing and if the government will be able to raise the money it needs. Whatever be the answer, if the government’s borrowing plan is transparent and appears to meet the financing need, it should be hugely comforting.

This article was originally published on Moneycontrol. See original >